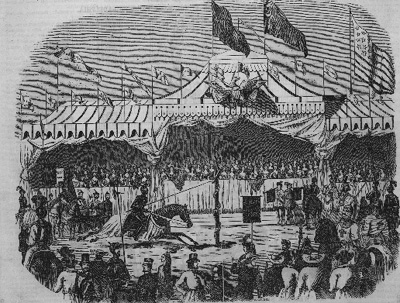

| If one were required to specify a date when tournaments really blossomed in America, the Gilmor estate on York road, just outside of Baltimore in 1840, provides part of the answer. Regarded as the "godfather of the Maryland, indeed Southern tourney" William Gilmor, while abroad, witnessed the famed Eglinton Tournament in Scotland on August 29, 1839. The following year Gilmor, a superb rider - handsome, rich, well-bred and well-read, hosted the most elaborate quintain tournament ever held on American soil.

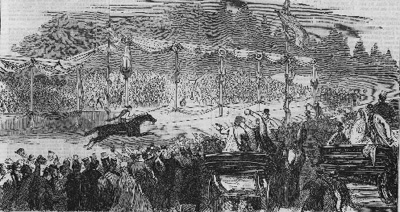

One of the first advertised, full-fledged ring tournaments, complete with rules, took place at Fauquier White Sulphur Springs, Virginia (now part of West Virginia) on August 28, 1841. So socially significant was this event that the ALEXANDRIA GAZETTE outlined its rules: One of the first advertised, full-fledged ring tournaments, complete with rules, took place at Fauquier White Sulphur Springs, Virginia (now part of West Virginia) on August 28, 1841. So socially significant was this event that the ALEXANDRIA GAZETTE outlined its rules:

A RING, properly adorned, will be suspended opposite the seats of the Judges, nine feet from the ground; which each champion will essay to transfix with his lance in knightly style, and bear away in chivalric triumph; each champion to commence his course at the sound of the bugle, at a distance not less than 75 yards from the Ring; and he shall have three trials of his skill and prowess, and shall ride at full speed.

The triumphant Champion shall, by direction of the presiding Judge be proclaimed by the Herald, followed with the sound of the Bugle, and an appropriate Air on the Band. Whereupon, the victor, remaining on horseback, shall present the Ring on the point of his lance to the presiding Judge, and shall receive from the latter, the Crown destined for the Lady, whom his choice will constitute the "Queen of Love and Beauty," in all knightly acceptation. He will then repair to the presence of the Lady of his choice, with a knightly retinue, and, dismounting before her, will place on her brow the crown won by his skill and daring; and will, thereupon, receive from her the Victor's Wreath, accompanied by a gracious Address, to which he will respond, as a true and gallant knight should do. Whereupon, the Herald will announce the denouement, followed by the Bugle, and a suitable Air on the Band.

Another early tournament, listed as the "oldest continually held sporting event in North America", at the Natural Chimneys in Mt. Solon, Virginia is reported by the Richmond Times Dispatch to have originated in 1821. It seems a certain local beauty would not choose between two suitors. Her uncle organized a tournament to settle the issue. The affair was such a success it became an annual event. This tournament is still held each year the third Saturday in August on the very same grounds. a tournament to settle the issue. The affair was such a success it became an annual event. This tournament is still held each year the third Saturday in August on the very same grounds.

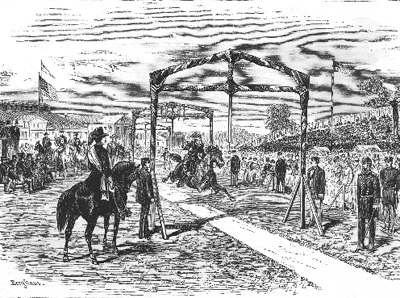

After 1840 tournaments could be found in every state and slightly civilized county south of the Mason- Dixon Line. See the invitation to a Grand Tournament and Ball as published in the Frederick Examiner, August 12, 1857. During the Civil War there was an understandable decline in activities. There is, however, an interesting account of a tournament hosted by an Alabama cavalry regiment at their winter quarters along the Potomac. They rode in rags and barefoot, but with great enthusiasm. There is a report of another famous Civil War tournament held on the lawn at Monticello near Charlottesville, Virginia in the fall of 1863. The Confederate soldiers and their ladies hosted a splendid tournament when the Yankees were bragging that even a crow couldn't fly across the valley without their consent.

After the war and well past the turn of the twentieth century, tournaments reigned supreme in the south as the unquestioned favorite pastime. Some even began to refer to the tournament as the "National Sport of the South."

Just as interesting as the origin of the tournament, are the reasons it became so immensely popular. In the 1700s, the gentry of Maryland and Virginia developed a formal, chivalric behavior code that was to have important connotations for the romanticism of the next century; they learned to "value the amenities of a genteel life". In the first half of the nineteenth century the world beheld the beginnings of a "romantic revival". Writers such as Yeats, Byron, Shelley and Scott glamorized romantic and chivalric notions. The full-fledged southern "code of chivalry" was a manifestation of this romantic movement, expressed in various forms - dress, literature, excessive politeness to women, florid speech, and a fanciful ideal of personal honor, and honor of their region. Gothic and mock medieval designs were favored in architecture. In their homes the southerners read Sir Walter Scott's books such as Ivanhoe and his other Waverly novels. In their fields they re-enacted his tournaments. The whole concept of reviving "medieval" tests of skill spread quickly throughout Dixie, where a long-standing interest in horses and horsemanship provided a ready-made backdrop. Tournaments offered an ideal occasion for romantic glorification of womanhood and the staging of pageants. Mark Twain thought Sir Walter Scott "set the world in love with dreams and phantoms," and that he had so large a hand in making Southern character, as it existed before the war, that he was in great measure responsible for the war women, florid speech, and a fanciful ideal of personal honor, and honor of their region. Gothic and mock medieval designs were favored in architecture. In their homes the southerners read Sir Walter Scott's books such as Ivanhoe and his other Waverly novels. In their fields they re-enacted his tournaments. The whole concept of reviving "medieval" tests of skill spread quickly throughout Dixie, where a long-standing interest in horses and horsemanship provided a ready-made backdrop. Tournaments offered an ideal occasion for romantic glorification of womanhood and the staging of pageants. Mark Twain thought Sir Walter Scott "set the world in love with dreams and phantoms," and that he had so large a hand in making Southern character, as it existed before the war, that he was in great measure responsible for the war

The tournament as an organized amusement gratified fundamental human desires. It offered, amid costumes and pageantry, competition that tested the skill and control of the participants, honored the victors above their peers and gave them a chance to share their distinction with the opposite sex, culminated in social expression through the dance. Beyond all this, there seemed to be a present and real sense of participation in the traditions of a colorful past, and perpetuation of the ideals of an ancestral race. Unlike most sports, which, whatever their history, remained games of the present, the tournament at its best never lost its association with former days. It offered, amid costumes and pageantry, competition that tested the skill and control of the participants, honored the victors above their peers and gave them a chance to share their distinction with the opposite sex, culminated in social expression through the dance. Beyond all this, there seemed to be a present and real sense of participation in the traditions of a colorful past, and perpetuation of the ideals of an ancestral race. Unlike most sports, which, whatever their history, remained games of the present, the tournament at its best never lost its association with former days.

|

|